By Wale Ojo-Lanre, Esq.

The first question some people will ask—already foaming in the mouth, already angry before thinking—is this: what is the problem of Wale Ojo-Lanre with Oyo State? Is he from Oyo? Is he not from Ekiti? Whatever. I am a Nigerian. By constitutional residence, historical immersion, and emotional investment, Ibadan is my town and Oyo State is my state. I have lived in Ibadan from January 3rd, 1991 till today, and God will punish me if I ever think evil of Ibadan and Oyo State. I sowed the most productive years of my life here. I laboured here. I reaped here. I buried friends here. I raised children here. I drank water, breathed dust, fought battles, and wrote history here. And let me say it without false modesty: nobody—living or dead—has promoted the tourism potential of Oyo State more relentlessly than I have. So yes, I reserve the moral, professional, and civic right to poke my nose into anything that affects, or pretends to affect, Oyo State.

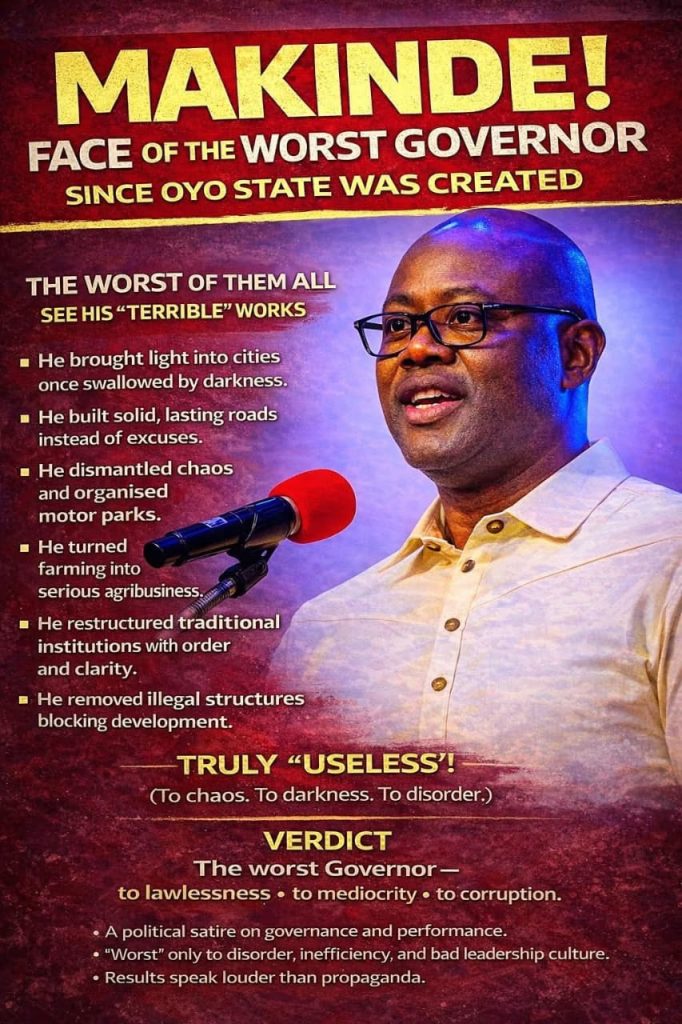

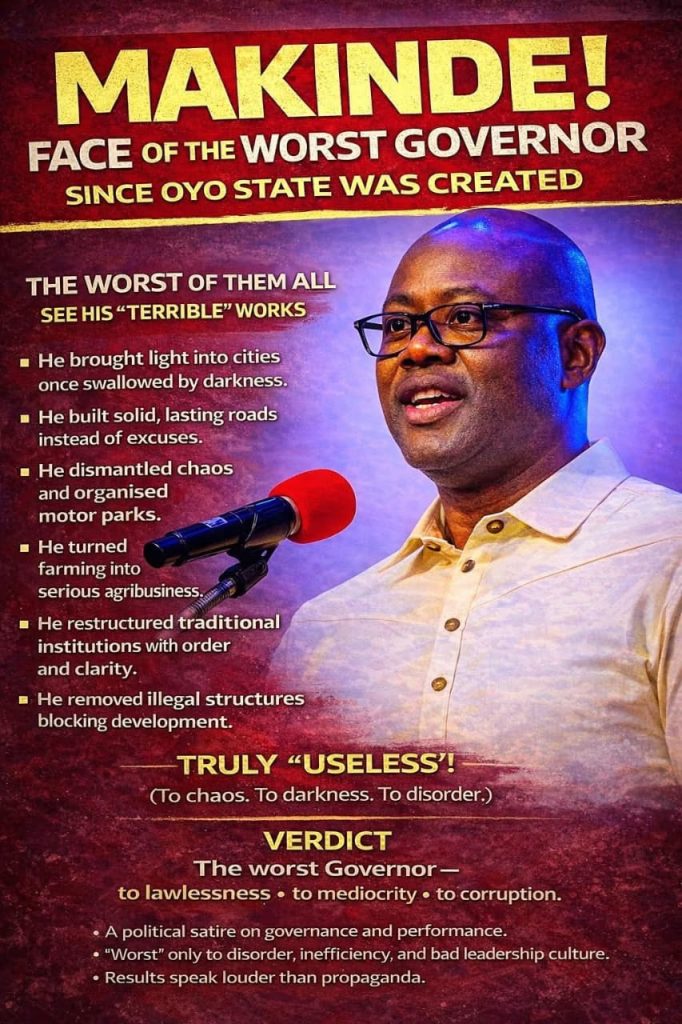

I joined the Nigerian Tribune in 1991 and will formally retire on January 3rd, 2026. I served two terms as the Number One Journalist in Oyo State—Chairman of the Nigeria Union of Journalists, Oyo State Council. So when I speak about the governments and Governors of Oyo State from 1991 till date, I am not guessing, I am testifying. And without mixing words, without diplomacy, without friendship discounts, I say it plainly: Seyi Makinde is the worst Governor Oyo State has ever had. Yes, the worst. Forget the fact that he is my brother. Forget that he is my friend. Forget that he once supported my NUJ chairmanship through Akeem Azeez, his media point man at the time. He did well personally, but personal relationship cannot silence public truth. Walahi talahi, Makinde is the worst.

He is the worst because he arrived and refused to govern the way Oyo State had been conditioned to expect. He refused to preserve chaos for political convenience. He refused to respect disorder as culture. Imagine a Governor with the audacity to remove illegal structures obstructing the realization of a massive circular road of immense economic importance, choosing urban logic over emotional appeasement, planning over pity, the future over present noise. In a society where illegality often hides behind sentiment, he showed no mercy. Then he went further and interfered with traditional council postures, insisting on clarity, order, and constitutional alignment, as if confusion was not a sacred inheritance. In a place where ambiguity feeds power, he chose structure, and that alone qualifies him as dangerous.

As if that was not enough, he declared war on darkness. He lit up Ibadan, Ogbomosho, Oyo, Saki, Iseyin—not for beauty, but so people could live without fear. Suddenly traders stayed out late, transport ran deeper into the night, the city breathed after sunset, and the night economy woke up. Darkness had been tradition. Fear had been culture. Makinde ruined both. Then he touched what many Governors feared most: the motor parks. Ibadan used to tremble at the mention of NURTW. Union thugs dictated peace. Blood was routine. Leadership disputes meant violence. Makinde said no. He proscribed, reorganized, removed sacred cows—including those people feared to name—and then, in his usual wickedness, built proper bus terminals and dragged loading activities off the highways into order. Roads remembered they were roads. Transport stopped holding the city hostage. Calm returned. Very irresponsible governance.

He was not done. He connected the state deliberately. Ibadan–Iseyin. Ogbomosho–Iseyin. Moniya–Oke-Ogun. Roads that feed markets, not headlines. Economic corridors, not ceremonial asphalt. While others chased ribbon-cutting roads to their mistresses chalet Makinde built routes that move food, people, and commerce. And because wickedness must be complete, he interfered with traffic. For decades, Ibadan traffic had been treated like fate—complained about, never solved. Junctions punished patience. Gridlock was identity. Makinde redesigned junctions, installed synchronized traffic lights, built flyovers where excuses once lived, and suddenly movement became predictable. Congestion lost its authority. In Nigeria, where suffering is often accepted as destiny, this was unacceptable.

He even interfered with memory. Streets that once meant nothing began to carry meaning. Infrastructure stopped being anonymous. Roads, junctions, and parks began to honour Ibadan’s builders and icons, turning the city into a living archive instead of a forgetful sprawl. How dare a Governor give a city identity? And tourism—another unforgivable sin. Tourism in Oyo State used to mean abandoned sites and occasional festivals. Makinde changed the grammar. He treated culture as economy, not entertainment. Bower’s Tower returned from neglect. Agodi Gardens was sustained as value, not nostalgia. The World Sango Festival received structure. Igbo-Ora was deliberately branded the Twin Capital of the World. Tourism stopped begging for attention and started earning respect.

Still unsatisfied, he went after health. Instead of leaving people to sell land before seeing doctors, he expanded health insurance, strengthened primary healthcare in every ward, upgraded hospitals, and sent medical missions into communities. People began to visit hospitals before dying, not after. Mothers survived childbirth. Children survived infancy. This kind of order is dangerous in a country that feeds on emergency. Then he attacked agriculture—not with slogans, but with systems. He turned farming into agribusiness, attracted private investors, revived dead farm estates, trained youths, linked farms to roads, and made rural economy matter again. Oyo began to feed itself and others. Politics was no longer hungry.

And just when the city thought he was done, he tampered with housing and space. Instead of letting Ibadan choke itself to death, he opened new corridors, enabled planned estates, partnered with private developers, and quietly pushed the city outward in an organised way, away from slums, away from chaos, away from the familiar disorder that politicians exploit. He even had the audacity to imagine a future economy beyond roads and farms—a place for ideas, skills, creativity, and productivity—laying the groundwork for a Knowledge, Arts and Productivity Village, as if young people should be trained, housed, and employed instead of being weaponised.

Security followed the same stubborn pattern. He strengthened Amotekun, backed it with vehicles and logistics, deployed technology, emergency lines, surveillance, and deterrence through light. He dismantled political thuggery and reclaimed public space. The state began to breathe. Fear began to retreat.

Seyi Makinde’s greatest crime is simple: he governs quietly, he works silently, and results shout on his behalf. He denied mediocres the comfort of chaos. He refused to fail loudly. He succeeded annoyingly. So yes, call him the worst Governor ever—worst to darkness, worst to thuggery, worst to illegal structures, worst to traffic chaos, worst to nameless streets, worst to abandoned tourism, worst to broken healthcare, worst to subsistence farming, worst to unplanned housing, worst to idle youth, worst to empty slogans. But to governance? History will be very cruel to those who pretended not to see. Àṣọ tí a yálọ tí kò bá jù ni, a fọ ẹni. Borrowed governance exposes the borrower. Makinde wore governance in his own size,.

It is a real Omititun!

God bless him