By Frank Meke

Dateline: Ilorin, Sunday, June 8 — the third day of Eid el-Fitr or Eid al-Adha celebrations in the ancient city of Ilorin.

Our convoy was modest in size, but we were armed with VIP invitation cards, which granted us access to one of Nigeria’s most spiritually symbolic and unifying festivals — the Ilorin Durbar. At the Kwara Baseball Park in Adewole, where the event had been relocated for crowd control, thousands had already gathered, stretching some three kilometres deep.

My anxiety about crowd control was real — and understandable. In a country where such logistics often collapse under pressure, being swept up in the euphoria of a culture-loving crowd isn’t always fun. Yet, I was determined to witness what others might not see — the deeper meaning, the return on investment, and the intangible heritage of our people.

This was my first Durbar in Ilorin, and walahi, I came prepared — not just with my camera and notepad, but with an open heart to understand the spirit of the city. Ilorin, in its unique way, defies division. Here, tribe and religion yield to peace, commerce, and cultural harmony. I have family here, and I’m a regular — whether by road or air — drawn by the city’s cultural appeal and its rising status as Nigeria’s gastronomic capital. Fact-check me if you wish, but there’s no Amala like Ilorin’s, and no peppered rice like the one prepared by my host and sister-from-another-mother, Mrs. Bolaji Mustapha — President of NATOP (National Association of Nigeria Tour Operators).

Forgive the food talk — but Ilorin draws you in like that: its energy, its pulse, its unspoken promise of discovery.

Back to the Durbar.

Our convoy was led by Alhaji Mustapha — tall, regal, a man who drives with the confidence of a battle-tested general. I sat beside him, eyes flicking between camera lenses and the human sea around us. I wasn’t taking chances. After all, in Nigeria, anything can happen.

But the true General? That would be his wife, Mrs. Bolaji Mustapha — the Amazon of Nigerian tourism. I attempted to dance to the thunderous trumpets and drumming of local musicians. It didn’t work — I couldn’t keep up. So, I did what any culture-loving Nigerian would do — I tossed a Naira note (not ₦100, please!) to the blaring horns. The gratitude echoed in crescendos.

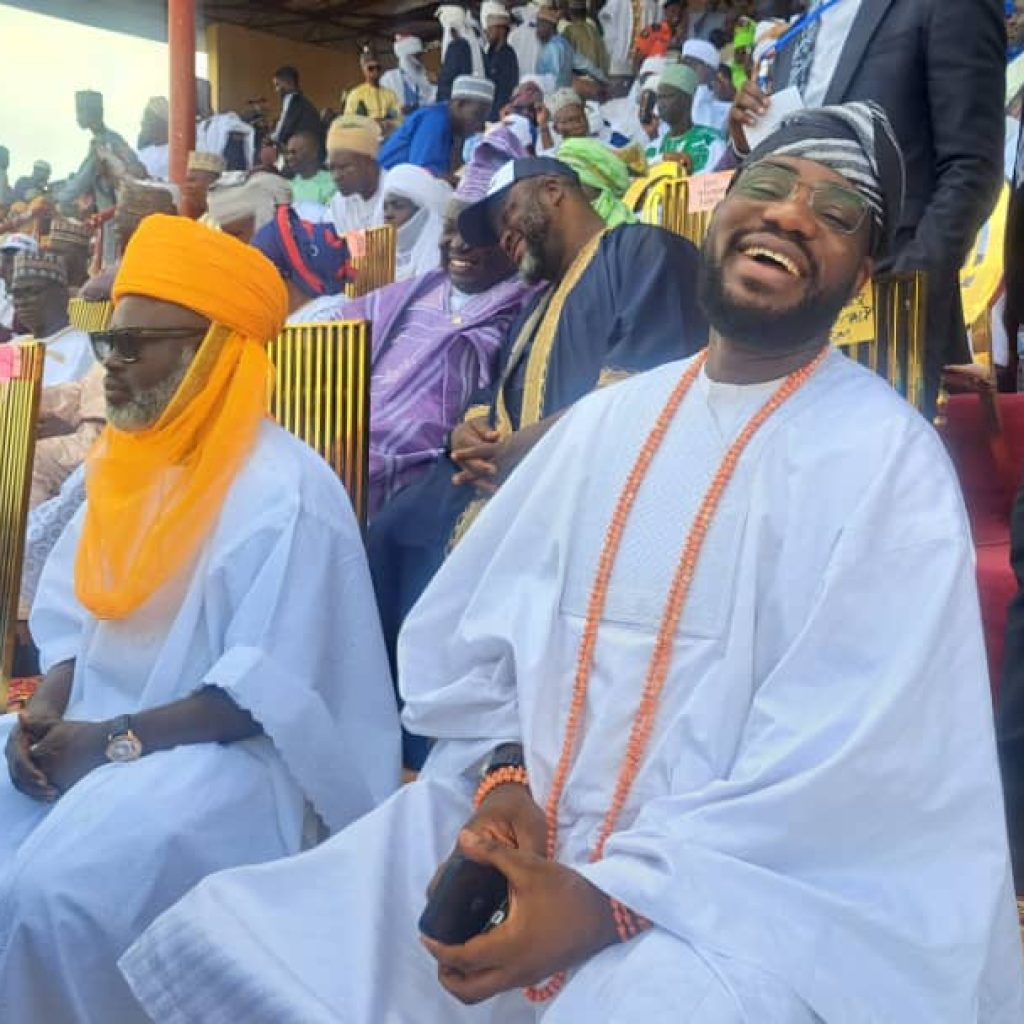

And then there was the beauty — the women of Ilorin, elegantly dressed in vibrant fabrics, exuding grace. The men, regal in their turbans and robes. The Durbar festival, I observed, isn’t just about heritage or horse riding. It’s a subtle matchmaking ground. Looking for a spouse? You just might find one here. But someone reminded me — here, a man can marry as many as he can love and honour. I wished them luck silently as I navigated my way to the seating area.

Cultural protocol is clear: men sit apart from women. I respected that, but couldn’t resist crossing the line briefly to greet my sister and colleague, Mrs. Nneka Isaac-Moses of Goge Africa. I whispered greetings to Mrs. Bola Shagaya nearby and waved discreetly to NTDA’s Jos Zonal Coordinator, Nnana Yakubu. Hugs? Not today — not in the city of Shehu. Lailai!

I also spotted Aare Abisoye Fagade — the newly appointed Director-General of NIHOTOUR (National Institute of Hospitality and Tourism). Passionate, connected, and always engaging, we shook hands and exchanged industry updates. My outfit — knicker, light shirt, bush cap — clearly marked me as a buttered tourist. I sat near Isaac Moses, and as seasoned tourism journalists tend to do, we began a quick review of the festival — until the ground erupted with booming gunfire.

I didn’t flinch — okay, maybe I ducked a bit — but I reminded myself, “I’m a warrior, too.”

Then, they came.

The cavalry. Mounted warriors. Horse riders charging in from all directions, their colourful regalia fluttering, their spears gleaming, their trumpets blaring. A spectacle of equestrian skill, courage, and coordination. The crowd roared in approval.

Militarily, Durbar is a symbol of readiness — a ceremonial parade of the Emirate’s strength. But here, it is also a cultural spectacle, an affirmation of heritage, unity, and loyalty to the throne.

His Royal Highness, Dr. Ibrahim Sulu-Gambari — Emir of Ilorin, retired Appeal Court Justice and scholar, turned 85 this April. He leads a harmonious kingdom of Yorubas, Hausas, Nupes, Barubas, and Fulanis. A true bridge-builder. A Nigerian dream made flesh.

The crowd surged again — this time, toward the gates. And then it happened.

A chant. Gentle at first. Then louder. “SHEHU! SHEHU!! SHEHU!!!” The entire park shook with the thunderous echoes of that name. SHEHU had arrived — seated in a majestic horse-drawn cart, surrounded by a regal cavalry. The reverence was overwhelming.

The chant grew stronger. Louder. The air thickened with awe and admiration. The crowd bowed, danced, wept, and waved. The Emir waved back, enduring the scorching sun just to honour his people.

I whispered a prayer: “God, grant Nigeria leaders like this. Leaders who love and show up for their people.”

As the Emir departed, the chant resumed — SHEHU! SHEHU! SHEHU!

And so ended the Durbar — not with a whimper, but with a storm of devotion, cultural pride, and the echo of a name that binds a kingdom together.

I salute you, Shehu — the Emir of Ilorin.